The Many Lives of Elizabeth Simcoe

- kmabel6

- Dec 7, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 30

While John Graves Simcoe has been a figure for derision in Canada to all but late-nineteenth century imperialists, his wife has always been given much more positive press. Why? In this little essay, I want to explore how Elizabeth Simcoe's life has been represented and used over time. Changing ideas about who she was and why she mattered tell us as much about the historical context of each observer-historian as they do about the woman herself.

Possibly Charlotteville on the north shore of Lake Erie by Elizabeth Simcoe.

The somewhat enigmatic remains of a campfire here are suggestive of our subject.

What remains of Elizabeth Simcoe’s life for us to interpret?

Source: Archives of Ontario F47-11 (available on Wikimedia Commons)

As I noted in November’s blog entry, J. Ross Robertson provided readers with the first book-length introduction to Mrs. Simcoe, primarily to ensure himself a place among the social elite of Toronto while promoting support for Canada’s imperial connection to Britain. Of course, he did not promote the story quite that way. He suggested that readers would be interested in her because she provided a lively glimpse into the social life of Upper Canada – as opposed to the tedious political and constitutional fare that dominated bookshelves in the day.

Robertson’s contemporaries preferred a slightly different reason to celebrate Elizabeth Simcoe. And it was this understanding that would dominate for the next century. It was her depiction of the landscape (in both visual and verbal form) that mattered.

Henry Scadding offered readers their first glimpse of Mrs Simcoe in his 1873 effort, Toronto of Old. He says little about her other than to stress her “skill and facility and taste” in drawing and painting. On the one hand, it made her a great help to her husband (who was the one who really mattered, after all) by producing maps. On the other hand, Scadding observed, she left for posterity “views of Canadian scenery in its primitive condition.”[1] This single focus is extraordinary, given that Elizabeth Simcoe had been known to him since boyhood and her patronage had educated him and found him a place in the Canadian church. The very fact that his description of her is so limited gives us a clue about the importance of his emphasis on her “views.”

Henry Scadding (1813-1901), c. 1860

Source: Toronto Public Library DC-OHQ-Pictures-S-R-726

Scadding’s real interest was not Elizabeth Simcoe. Rather, he wanted fellow Torontonians to appreciate how much their world had changed in a relatively short time. The “primitive” landscape had been remade into a “civilized” world of agriculture, commerce, and industry. Canadians in the late nineteenth-century could use Elizabeth Simcoe’s work as a yardstick for measuring “progress.” And they could be very proud of themselves.

Some fifteen years later, retired lawyer David Breakenridge Read gave readers the first few reproductions of her artwork, accompanying his biography of John Graves Simcoe. She was, he assured readers, “an accomplished and accurate artist” who gave us images of Upper Canada that we could trust to represent the state of the place.[2]

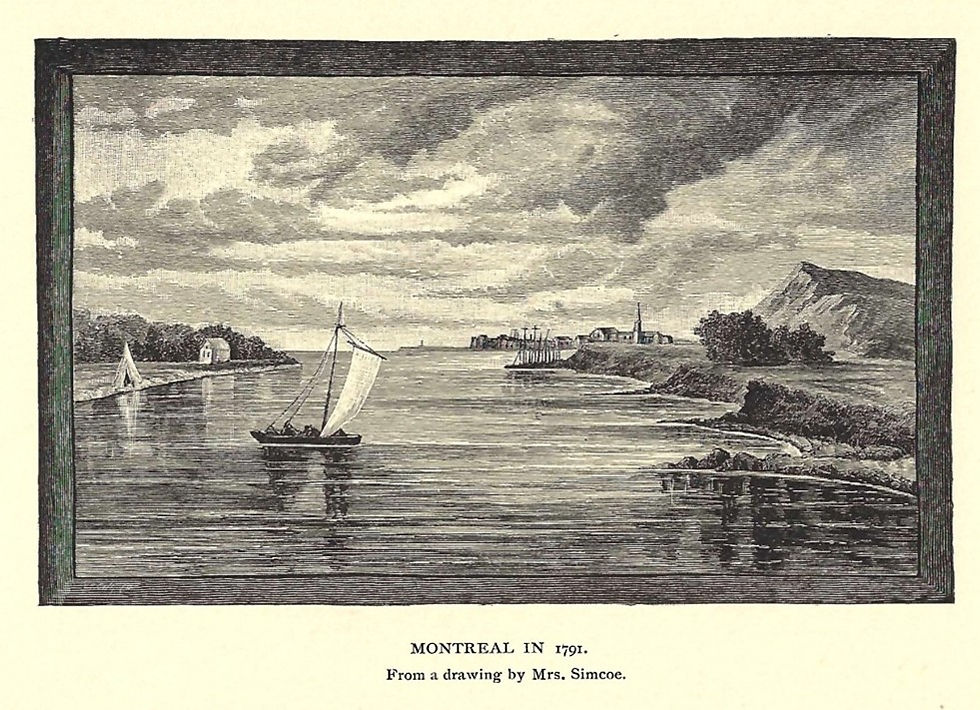

One of the illustrations in Read’s biography.

Note that these were not reproductions of originals

but woodcuts that he had obtained from a colleague, based on the Simcoe sketches.

Hardly a primary source as we now understand it.

Read was not interested in the aesthetics of her work but only its use as an historical source. He was writing at a time when university-based historians were making claims to a professional and scientific approach to history. Accuracy and reliability of sources was one of its major tenets. And while Read was not one of their number, he obviously wanted his biography to be taken seriously and measure up to the new standards. Still, Mrs. Simcoe served a purpose little changed from the earlier one. She told readers how much had changed.

David Breakenridge Read (1823-1904) in a portrait painted in 1858 while he was briefly mayor of Toronto.

Source: City of Toronto Collections

In 1910, civil servant and poet Duncan Campbell Scott made similar use of Mrs. Simcoe in his biography of John Graves Simcoe for the Makers of Canada series. Scott found her written descriptions of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and the Kingston barracks helpful, and, as had others before him, saw Elizabeth primarily in her role as the Lieutenant Governor’s silent sidekick. For Scott, Mrs. Simcoe was a trustworthy recorder of history because she came from a “very honourable” family that traced its roots “in a direct line to the ancient kings of North and South Wales.” Even better, her father had served with General Wolfe at Quebec, “which fact proves his worth as an officer.”[3] Clearly Scott (like Read before him) wanted to be taken seriously by the newly professionalized historians. But his attempts were rather ham-fisted.

It wasn’t until after the First World War that Elizabeth Simcoe began to emerge as a person in her own right – not just as Governor Simcoe’s consort or the provider of historical evidence.

In 1926, William Renwick Riddell finally completed the biography of John Graves Simcoe that Ross Roberston had once hoped to write. While Elizabeth Simcoe is mostly just a passing reference in the larger narrative of her husband’s life, Riddell did point out that it was her money that bought the Wolford estate in Devon (earlier writers had implied it belonged to her husband even before their marriage). And she had opinions of her own, as in her “great shock” when General Simcoe accepted a posting to Haiti.[4] For some curious reason that I have yet to decipher, the longest section about her in the book dwells on the knowledge of herbal remedies that she acquired in Upper Canada, making her “an authority in simples” as is claimed in the index.[5]

William Renwick Riddell (1852-1945) in his professional garb.

Source: Osgoode Hall collection

It was not until the mid-1960s that Canadians rediscovered Elizabeth Simcoe. There was a flurry of interest, extending the story of her life but remaining rooted in the earlier interpretations and focus.

Toronto scholar Mary Quayle Innis published a new version of The Diary, more extensive and carefully arranged than J. Ross Robertson’s. Academic historian F. H. Armstrong reissued Scadding’s Toronto of Old as a pared-down volume with a helpful introductory essay and much additional biographical material, including on Mrs. Simcoe. Journalist Marcus Van Steen published Governor Simcoe and His Lady using what today would be called creative non-fiction to imagine aspects of Elizabeth Simcoe’s life not revealed in her writing. For the first time, he offered readers nearly ten pages on her life before and after her marriage.

The dust jacket of Van Steen's book uses as a backdrop the monument to the Simcoes at Niagara-on-the-Lake (near old Navy Hall).

The many and varied monuments and plaques for Elizabeth Simcoe will be explored in a future blog.

But these were all very much like the older studies. For the male historians, Elizabeth Simcoe was the hostess at her husband’s side. Only Mary Quayle Innis finally portrayed Elizabeth as a person in her own right. And yet, even then, the publisher marketed the diary as being of “extraordinary interest” for recording “great events in a familiar way” and revealing “a side of Canadian history that is little known.”[6] Innis clearly liked and admired Elizabeth Simcoe but ultimately saw her importance as an “observer” of history, not as an active maker of it.[7]

Meanwhile in England, rather more critical perspectives were emerging. In 1953, artist and writer Averil Mackenzie-Grieve published a study of the role of women in British colonization. Each chapter was devoted to a woman in a different colony. Elizabeth Simcoe is Chapter 4. Grieve proposed (as Innis later would), “She was primarily a chronicler of the colonial history which was being made by others.” And while she allegedly was not herself “a contributor to Canadian life,” she was able to “record it objectively” and give us a “valuable” perspective on the colonial experience.[8]

At the same time, Grieve found the Simcoe diary “dull” and “unimaginative.” Its author “never investigated for herself” and had no real curiosity about other people.[9] As for the world Elizabeth Simcoe described: “Chinese porcelain in a hut of branches, Stowe tapestries in a log cabin, Mrs. Simcoe accepted these extraordinary contrasts as perfectly ordinary.” Grieve was not really critiquing Elizabeth Simcoe here. These contrasts, Grieve argued, were “but an extreme simplification of the antitheses which made up Georgian life.” To this kind of Englishwoman, “over-refined luxury” was a counterpart to “a practical realism” and “a tough resilience to primitive conditions” that made colonial life possible for the English and “formed the basis of an indigenous culture.”[10] Elizabeth Simcoe’s life provided an entrée into understanding how colonialism worked on the ground – or rather, how it worked for the British colonizers. Grieve was explaining how colonialism “worked” in a practical sense. She was not critiquing it as we do today.

Another (and much sharper) commentary on Elizabeth Simcoe came from the pen of art historian Roy Strong in 1967. He was then working at the National Portrait Gallery in England and was mightily amused by her “views of Canada,” in which she churned out images “copied from that high priest of the picturesque, the Rev. William Gilpin.” She (and several other interpreters of the Canadian landscape whom he names) “evoke the word pictures of Mrs. Radcliffe describing Alpine scenery in the Mysteries of Udolpho.” He went on,

Water-falls crash down ravines, trees trail in limpid waters, cliffs

of rock rise to fantastic heights, and one peers down on to idyllic

tiny towns from hill sides embowered with greenery. It is all “awe”,

“terror”, and “sublime” …[11]

Earlier Canadian writers might have praised her “objectivity” and “accuracy.” For Englishman Strong, she was simply a copyist, interpreting her “views” through the eyes of cliché: ideas that no longer suited the modernist aesthetic. She had nothing of value to say to a world that had long ago passed her by.

As academic critiques of imperialism and colonialism mounted in the 1970s and 1980s, Elizabeth Simcoe could no longer be considered simply passé. She (as both wife and record-maker) became an active agent of the imperial project – and hence worthy of our approbation, not admiration. Her “views” were now interpreted as an attempt to stamp the British imperial gaze on the Canadian landscape. Her comments on Indigenous peoples were selectively quoted out of context to make it appear that she was a racist. She and her husband arrived in a whirlwind of teacups and finery, renamed all the Indigenous places, and departed after just four years, having managed to create permanent havoc – havoc which would take an armed rebellion and much political grief to overcome. Not a pretty picture.

Amid all this angst. Mary Beacock Fryer published a biography of Elizabeth Simcoe that

for the first time went beyond the now well-known (and much mocked) diary. Fryer explicitly rejected the image produced by those who “ridiculed” imperialists and who set Mrs. Simcoe up as “an incongruous figure in the wilderness with her good china and her ballgowns.” By considering Mrs. Simcoe’s life before and after the Canadian sojourn, Fryer argued that Elizabeth is better understood as “the typical gentlewoman of her time.” She was an artist shaped by the “Age of Reason” in early life and an Evangelical who “found meaning in service to her church” in later years.[12]

For Fryer Mrs. Simcoe was simply “a remarkable woman” who ought to be known for her own sake. Although Fryer doesn’t say so directly, the biography seems to fit into the growing collection of women’s biographies that were emerging from the sub-discipline of women’s history in the 1980s.

During the following decades, women’s history dissolved into gender history more broadly and biography fell out of favour as radical postmodernist theories challenged the hidden assumptions behind traditional historical writing. Elizabeth Simcoe disappeared.

In 2015, she appeared again – in a new and yet old, established way. Celebrated historian Margaret MacMillan proposed that individuals do, indeed, play a role in making history. It isn’t all about representations or hidden structures or cultural systems. In History’s People, we meet some of those individuals who made history, organized according to personality types. Elizabeth Simcoe appears primarily in the chapter on “Curiosity.”

For MacMillan, Elizabeth represents the women of empire who “accompanied” (not “followed”) their husbands to “all corners of the world,” facing challenges we would “find overwhelming” while managing to “take an active interest in their new surroundings.”[13] Certainly not Averil Mackenzie-Grieve’s insipid and unimaginative colonial wife!

Elizabeth Simcoe returns briefly in MacMillan’s chapter on “Observers” for her views of “Toronto when the very first buildings were going up.”[14] There are echoes here of the late nineteenth century interpretation of Elizabeth Simcoe’s value in showing us “how far we have come.” At the same time, MacMillan is far more nuanced in her appreciation for what these stories tell us about “the clash between the Old World of Europe and the new one” and the bigger story of the “evolution” of Canada and “the search for what it is to be Canadian.”[15] Re-framed questions for a new generation.

Apart from Mary Beacock Fryer’s work, Elizabeth Simcoe has been understood entirely in the context of her Canadian sojourn. And each interpretation is ultimately drawn from a reading of her diary (through Robertson or Innis). She has been an objective and accurate observer – or an arch-colonialist who saw everything through imperial eyes. She has been a talented artist – or an imitative amateur sketcher. She has been utterly lacking in curiosity about the world around her – or a profoundly curious person open to new ideas in a new world.

Elizabeth Simcoe has been whatever we needed her to be. The one thing that she has never been is a real person, complex and multifaceted, trying to come to terms with the often-frightening world in which she found herself.

******************************************************************

NOTES

[1] Henry Scadding, Toronto of Old (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1966), 171. This is an abridged version edited by F. H. Armstrong from the 1873 edition.

[2] D. B. Read, The Life and Times of Gen. John Graves Simcoe (Toronto: George Virtue, 1890), 138.

[3] Duncan Campbell Scott, John Graves Simcoe (Toronto: Morang & Co., 1910), 40.

[4] William Renwick Riddell, The Life of John Graves Simcoe (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1926), 298.

[5] Ibid. Pages 367-8 in the text provide a long list of these “simples” and their uses.

[6] From the dust jacket to Mary Quayle Innis (ed), Mrs. Simcoe’s Diary (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1965).

[7] See page 2 in Innis’s introduction.

[8] Averil Mackenzie-Grieve, The Great Accomplishment (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1953), 204-5.

[9] Ibid., 156.

[10] Ibid., 176.

[11] Roy Strong, “Far Away Places,” The Spectator (20 July 1967), 20.

[12] Mary Beacock Fryer, Elizabeth Postuma [sic] Simcoe (Toronto & Oxford: Dundurn Press, 1989), 240.

[13] Margaret MacMillan, History’s People (Toronto: Anansi, 2015), 225-6.

[14] Ibid., 299.

[15] Ibid., 309.

Comments